When building a business or software, it is easy to make assumptions about what the market will want or how users will interact with your product. Recently, the concept of the Lean Startup Experiment has emerged to help us explicitly acknowledge these assumptions and construct small experiments to validate our assumptions. Here at SEP, we refer to these activities as Validated Learning.

We’ve been looking for a good opportunity to practice running experiments, so we decided to try it internally as part of an effort to increase blog participation within the company. It’s one thing to read about the process in a book, but actually running a lean startup experiment is quite a challenge.

Blogging is something that SEP has struggled with. It’s difficult to convince a group of engineers that their experiences are worthy of being shared and that you don’t have to be an expert on a subject, just a little further than someone else. From a marketing and recruiting standpoint, blogging helps bring in leads for projects, as well as applicants for job openings and internships.

Over the past few years, we’ve heard several recurring answers to the question of “Why don’t you blog?”. Some of them seemed like they could be addressed with some kind of new policy or system:

- I don’t know what to write about, if someone told me what to write about I could probably do that.

- I don’t have any extra time to write a blog post because I’m on billable work

A small group had a meeting to determine if we could think of any ways to increase blog participation. Among the group several ideas were generated, however, if we use some of the Lean Startup thinking, these were just hypotheseses. We were making a lot of unvalidated assumptions – we thought we knew if something would be effective, but we had no real evidence to support it.

Instead of voting amongst the small group and rolling out some policy, we decided to run two experiments. Using the Experiment A3 template, we formulated two hypotheseses: one to address the lack of blog post ideas and one to address the issue of time accounting. I’ll be detailing the first experiment today.

One unexpected outcome of simply writing down our assumptions on paper was that we were forced to think about the “safety” of the experiment. What would be the worst case if someone were to “abuse” the system? How would we know when to give up on an experiment that didn’t seem like it was working? Are the changes we make something that could be undone? What are the potentially negative side-effects?

In our case, the experiments were not particularly “dangerous” but you can imagine that some experiments might have more impactful side effects (if you run an experiment that causes you to lose 20% of your customers, that is a big deal).

Experiment Name: Daily Blog Standup

What do we want to learn and why?

Blogging is good for marketing and recruiting, but participation is low amongst engineers. We want to learn if having a daily blog standup will increase participation.

Hypothesis:

If we have a daily standup, at least one person (outside of the experiment runner) will attend at least 3x per week.

Materials and method:

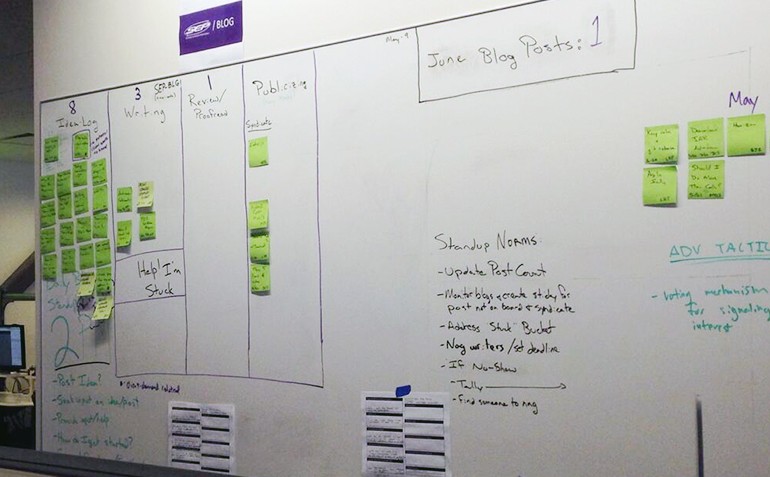

We will create a “blogging board” on the wall where the standup will take place. We will track attendence using a simple checkmark on a calendar to indicate if at least one person attended. We will fill the “backlog” of the board with a list of potential blog post topics.

Experiment safety:

In the worst case, we “waste” 5 minutes a day if no one shows up at the meeting. 25 minutes a week of potential lost time is not harmful. We will stop the experiment if no one shows up for 10 days in a row.

What happened?

We ran this experiment for nine weeks (roughly over the months of June and July). Of the nine weeks, four weeks had attendence over the threshold (3x per week) and five weeks did not. However, every week had at least one day in which someone attended.

Of the 23 potential blog ideas in the “backlog”, 7 of the ideas were turned into actual blog posts. My perception was that no one was using the ideas from the list, so it was incredibly important that we tracked the numbers. Without doing the formal tracking, I would have said that the idea list was a failure, but the data shows that it was not.

What did we learn/validate?

A daily standup was probably too frequent. Attendence at the standup did not always equal participation; many of the meetings were just a few people checking in on the status of their posts, but progress wasn’t always made.

We observed that if people saw a small group gathering for the standup, they were more likely to come over. We did not do a great job of advertising the standup (only mentioned one time in a company-wide email) and we did not make a mass calendar invite.

Some of the suggested topics proved to be useful and moved quickly from idea to finished blog post, while others lingered for the entire duration of the experiment. We also had a large number of posts that were written during this time that were not from the original idea list.

We had created an adhoc “publishing workflow” on the board using a Kanban-like system. Posts could move from the idea column to in-progress to review to published. In practice, posts did not move through the board in a smooth process – in fact, most posts went straight into the published column. Nearly every new attendee at the meeting also asked about the columns and there was general confusion about the process.

What’s next?

Some ideas for future iterations of this experiment:

- Try a weekly meeting instead of daily

- Rework the blogging board (it was too complicated)

- Try a quarterly email instead of a physical meeting

Experiment Outcomes:

Our hypothesis was invalidated – this format is not the final answer to improving blogging participation

Cycle time: 9 weeks

Cost: ~$200/week in “Time Money” (~30 minutes per week for ~4 people)

In hindsight, our hypothesis did not exactly align with our experiment. We were actually trying multiple solutions at once: a daily standup, a Kanban-like blogging workflow, and a post idea backlog. This made it harder to separate what worked and what didn’t work. More reps with the process should help us to be able to design more targeted experiments.

We should have done a better job of advertising the meeting internally, whether that was more frequent communications, a mass calendar invite, or just going “desk-to-desk” to make people aware.

Running experiments was harder than I anticipated, but the important part is that we got some practice using the technique and we learned some key insights about our problem domain (blog participation). Having the experiment written down on paper helped us stay accountable to following through on our original ideas and was invaluable when we got together a few months later to review the results.

Our small group will be continuing to run more experiments; we are planning to try our a quarterly email next, as well as a new experiment more focused on how we can generate qualified leads from our blog.

If you’d like to try running your own Lean Startup Experiment yourself, fill out the form below to download the Experiment A3 form.